ASEEES, the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, held its annual convention from November 17-20, 2016 in Washington, D.C. This author was honored to be a participant in the scholarly roundtable

"The Carpatho-Rusyn Global Village".

This roundtable discussion took place on November 17, and the context for it was the following.

When Marshall McLuhan popularized the concept of the global village in the 1960s, he anticipated that the rise of new media would allow for the instantaneous communication among individuals on all sides of the globe and bring about village-like networks in a virtual space. Similarly, Benedict Anderson has emphasized the role of the proliferation and circulation of print media, in particular, the newspaper, in constructing the concept of the nation. While the Carpatho-Rusyns have never had a nation-state of their own, they have maintained strong global networks among individual villages spread out in several countries through the production of newspapers, magazines, almanacs, books, and – most recently – websites and social media pages. As such, this roundtable will investigate how Carpatho-Rusyns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries used print media to create international networks between home and abroad, explore the influence of religion on their maintenance of a transnational community, and examine the virtual village-like mentalities and behaviors present on the Carpatho-Rusyn internet today.

I gave one of five presentations that made up the roundtable. The slides and my commentary follow here.

Over the past two decades, in my research of the Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant settlements of the U.S. -- primarily Pennsylvania, but also New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Ohio, etc. -- in which I especially focused on chain migration from homeland villages to American towns, I have discovered many examples of "village consciousness" as expressed by Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants, and I would like to share them, and my interpretation of them, in the hopes that other scholars may find aspects of this topic that warrant and inspire further study.

|

| A typical Carpatho-Rusyn village. |

|

This phenomenon is hardly unique to Carpatho-Rusyns; other peoples in their pre-national or in their nation-building processes, especially among the Slavic peoples, referred to themselves similarly, for example Belarusians, Polishuks, and Polissians.

|

|

| "We are from here." |

|

| The Carpatho-Rusyn village. (Photo: Ivan Čižmar, Svidník, Slovakia) |

|

| (Photo: Ivan Čižmar, Svidník, Slovakia) |

While my maternal grandmother’s native village (Prykra, Svidnyk district, Slovakia) never had more than 100 residents, I documented more than 35 natives of the village who lived in or around their primary U.S. settlement of Passaic, New Jersey for at least a time, before World War II.

|

A list of passengers from an immigrant ship from Bremen arriving at Ellis Island in 1902. On board were 5 people from Prykra and several others from nearby villages like Medvedže, Krajnja Poljana, Hinkivci, and Pysana.

|

|

A list of passengers from an immigrant ship arriving from Bremen at Ellis Island in 1910. On board were 7 people from Prykra. With them were several countrymen from nearby villages Nyžnij Komarnyk and Krajnja Bŷstra.

|

|

Naturalization document for George Simchena, residing in St. Clair, Schuylkill County.

The document shows his birthplace ([Nyžnje] Solotvyno, Už County) as well as that of his wife (Korytnjanŷ, Už County), but also his race as "Russniak" and the fact that he and his family lived previously in Hazle Creek, Schuylkill County.

|

|

| Typical baptismal register of a Rusyn church in the U.S., that of St. Mary's Greek Catholic Church in Scranton, Pa. The conscientious pastor recorded not only the birthplaces of both the parents of the child who was baptized, but also the birthplaces of the godparents. In these records we can see that in many cases, people from the same village settled in the same place, and the godparents were also from the same villages. |

Study of the metrical records of the churches established and attended by Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants can also enable us to trace the migration within the United States of not only individual families but also people from the same village. In many cases this can be accounted for by migration to places inhabited by relatives or other natives of the same village, or by other places with employment opportunities by the same firm or in the same industry. For example, there were clear migrations between Simpson, Berwick, Lyndora, and McKees Rocks, Pa., especially by people from Habura, Zemplyn County, as they transferred between factories of the Pressed Steel Car Company and related sites making railroad cars.

We can also learn where certain church communities fractured along village lines: for example, the Russian Orthodox parish in Patton, Pa., which broke from the original Greek Catholic parish in 1904, was founded almost entirely by Carpatho-Rusyns from Zvala, Zemplyn County.

|

| Some Rusyn fraternal organizations, such as the Greek Catholic Union shown here, published lists of their deceased members that included their birthplace. Unfortunately, not all of them did so; some published similar lists that did not include birthplace. |

|

| These two examples are not village consciousness per se, but are a strongly related kind of regional/group consciousness. |

|

A typical Carpatho-Rusyn parish cemetery.

(St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Cemetery, Barnesboro / Northern Cambria, PA) |

|

An example of a Rusyn immigrant gravestone with birth village inscribed.

Grave of Prykra native Paraska (Breniš) Limnjanska, 1889-1918, and her husband Andrij Limnjanskŷj from Vilšavka-Bukovec. They died just one week apart during the Spanish Influenza epidemic. (Paraska was this author's great-aunt.)

|

|

Grave of Mychal Kyca, born in Konjuš, Už County, Hungary.

(St. Mary Russian Orthodox Cemetery) |

|

Grave of Pavel Matjaš, born in Čertižne, Zemplyn County.

(St. Michael GC Cemetery, the oldest Rusyn cemetery in the U.S.) |

|

Grave of Gregor Babyč, born in Kryčovo, Maramoroš County. (Redstone Cemetery)

The Orthodox parish in West Brownsville, founded in 1917, used this cemetery for several years. Of the Rusyn immigrants buried here, 6 had their village on their tombstone and most of them were from either Kryčovo or Čumal'ovo, Maramoroš County. |

|

| St. John the Baptist Russian Orthodox Cemetery in Mayfield, Pa., is one of the largest Rusyn immigrant parish cemeteries in the U.S., and also the one having the most tombstones with the deceased's village of birth included on it. |

|

The Mayfield parish cemetery has 55 extant stones with the person's birthplace indicated. Of these, 10 are from Peregrymka, Jaslo

County, or 18% of all those with the birthplace noted.

|

|

| For example, the grave of Pavel Hadžinskij, from Peregrymka, who died in 1915: |

|

| The grave of John Čajkovskij, written in the Latin script, born in Halbiv (or "Habov"), Jaslo County, who died in 1900. |

|

St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Cemetery in Frackville, Pa. (of the church in Maizeville) has 33 extant tombstones of Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants whose birthplace is inscribed. Of those 33, 10 stones, or 30%, say the immigrant was born in Ščavnoj, Sanok County.

|

Some other cemeteries have both a relatively large number of tombstones with birthplaces on them:

- St. Mary Cemetery (Waterbury, CT) - Orthodox: 13 stones

- Ss. Peter & Paul Cemetery (Ansonia, CT) - Greek Catholic (Ukrainian): 14 stones

- Ss. Peter & Paul Cemetery (Punxsutawney, PA) - Greek Catholic: 14 stones

- St. Michael Cemetery (Saint Clair, PA) - Greek Catholic, later Orthodox: 17 stones

- St. Michael Cemetery (Jermyn, PA) - Orthodox: 18 stones

- St. Michael Cemetery (Shenandoah, PA) - Greek Catholic (Ukrainian): 39 stones

And some have a large percentage of the birthplace-inscribed stones of people from the same village:

- In Ss. Peter & Paul Cemetery, Punxsutawney, PA -- 5, or 36%, are from Čirč, Šarys County;

- In St. John the Baptist Cemetery, Mayfield, PA -- 10, or 18%, are from Peregrymka, Jaslo County;

- In St. Michael Cemetery, Shenandoah, PA -- 5, or 13% are from Hančova, Gorlice County, and 3, or 8%, are from Bodnarka, Gorlice County.

|

| While the transition to English tombstone inscriptions coincided with the end of birthplaces being included on them, some Carpatho-Rusyn descendants have placed more recent tombstones on their ancestors' graves that include birthplace. (Gravestone of Marja (Brenišin) Pisančik in St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Cemetery in Barnesboro, PA) |

|

| In addition to tombstones, some other monuments mark the donors' birthplace. This cemetery altar cross at St. Michael's Greek Catholic Cemetery in Sharon, PA, was given by parishioners born in Zavadka, Spiš County. |

|

| This set of windows in St. Michael's Russian Orthodox Church in Mt. Carmel were given by natives of four different villages in the western part of the Lemko Region (Grybow County). |

|

| Window in St. Mary's Greek Catholic Church in Trenton, N.J. |

|

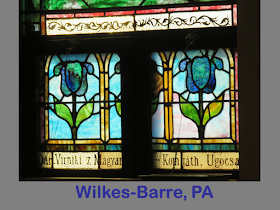

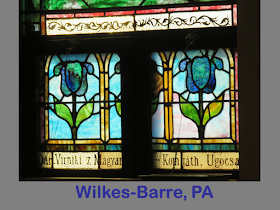

| Window in St. Mary's Greek Catholic Church, Wilkes-Barre, given by parishioners from Velyki Kumnjatŷ, Ugoča County. |

|

| Window in the choir loft of St. Mary's Greek Catholic Church, given by parishioners from Vlachovo, Ugoča County. |

|

| Window given by natives of Zariča, Ugoča County. |

|

| This was actually one of two separate windows given by natives of Zariča. |

|

| Window given by natives of Hreblja, Ugoča County. |

|

| Window given by natives of Iršava, Bereg County. |

|

| Window given by natives of Mydjanycja, Bereg County. |

|

| Windows given by natives of Sil'ce, Bereg County. |

The earliest such collection may have been the one taken up in 1907 for items for the church in Kamjunka, Spiš County. Some were taken up in the years immediately after World War I, but most were in the 1920s and 1930s.

The large majority seem to have been for repair, renovation, or building of churches and parish homes, or purchase of church bells, but some were for national causes like cultural centers and reading rooms.

Unsurprisingly, these collections abruptly ceased with the onset of World War II, and despite widespread destruction in many villages of Carpathian Rus' in the war, very few were conducted afterwards. I have found information on 5 taken in 1947, 2 in 1948, and 1 in 1949, all for villages in then-Czechoslovakia.

Finally, with some thawing of government restrictions in the 1960s, a few collections were conducted. Some of the last were for the church in Peregrymka, Jaslo County, in the early 1960s and continuing into the 1970s, and a few for other Lemko villages in the 1960s.

These were primarily publicized through the Rusyn immigrant newspapers, but usually hewed to adherents of one national orientation, that is, notice of a collection might appear in the RBO's

Pravda but not in the UNA's

Svoboda, or vice versa.

|

| List of donors in the Amerikansky Russky Viestnik to a collection taken up in Lyndora, Pa., for the church in Čabynŷ, Zemplyn County. Many surnames of Čabynŷ families appear in the list, but so do families from Habura, Medžilabirci, etc., who were also present in Lyndora in significant numbers. The four collectors named at the end were all born in Čabynŷ. |

|

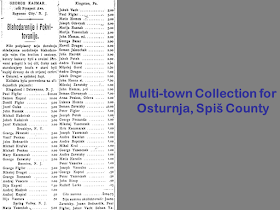

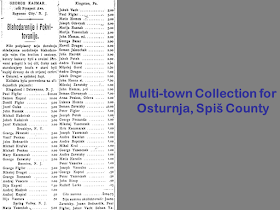

| This collection was taken up in several U.S. towns where natives of Osturnja had settled -- but primarily in Kingston, Pa. |

|

| This collection report for a Zemplyn County village taken up in Pittsburgh indicated the native village of the donors, grouping them by village, almost all of which were neighboring villages of Roškivci. |

|

| Some memorials in the homeland commemorate these assistance campaigns from the U.S., naming donors and the amounts given. |

Clubs in Cleveland for natives of individual Rusyn villages in the Prešov Region were founded by the immigrants from Bajerivci (1926), Biloveža (1931), Jakubjanŷ, Cernyna, and Šambron.

Similar clubs existed elsewhere, such as the Tylawa Club in Jersey City, N.J., and the Russian Brotherhood J.K.W. (Jastreb, Kyjov, Wislanka) of Bridgeport, Ct.

Social events for natives of certain villages, such as picnics (or

kermeš) and reunions were organized by these clubs or by informal networks of village natives.

|

| The first "Losjanskij Kermeš" was held in Pricedale, Pa., in 1941 and continued for several years. In 1998 the event was revived and has been held annually in that area ever since. |

|

| Village natives in the U.S. began to publish monographs on the history of various villages in the 1960s; these examples originated from members of the Lemko Association, most of whom were post-WWI immigrants who had a more developed sense of national identity at a time when older Rusyn immigrants were concealing their identity. |

|

| This 1981 publication came from an early Rusyn immigrant to Minneapolis who managed to recall the names of several hundred Rusyn immigrants and where they originated. |

The availability of resources online for genealogy and networking, and personal cross-Atlantic ties between villages and their natives/descendants made possible a new collaboration: village history monographs published in the homeland that with the assistance of Rusyn Americans contained detailed information on the life of village natives past and present in the U.S., such as these two about Slovakia Rusyn villages Prykra (2006) and Orjabyna (2007).

|

| Recent years have seen a proliferation of village-specific websites and especially Facebook groups. In fact, there are currently more than 35 Facebook groups of this type, some run by an individual in the village (usually separate from an official village page), others run by a descendant of the village or by a village native living elsewhere. Postings on these sites tend to be in various languages, including Rusyn and English. |

|

| The Rusyn village Litmanova, Slovakia, has three separate Facebook groups! The large number of Litmanova natives living abroad, especially in the U.S., seem to be a fairly tight-knit group with great pride in their roots and their home village. The phenomenon of the "Litmanova diaspora" and its development in the U.S. would make for a fascinating sociological and sociolinguistic study. |

|

As I discovered my roots and much later determined exactly what villages my Rusyn immigrant grandparents came from, it was my first visit to those villages that crystallized my own "village consciousness" that I have since tried to cultivate in others through my research on Rusyn chain migration and the resulting articles, talks, and my work on the New Rusyn Times.

(The author, at right, visiting his grandmother's village Prykra, Slovakia, in 1996.) |

Original material is © by the author, Richard D. Custer; all rights reserved.

Thanks for taking the time to post the picture of the Sharon, PA location's cross. On the stone of the cross it mentions Zavadka. How do you know the Zavadka in question is in Spis and is not the Zavadka near Male Zaluzice, Michalovce, and Lukcy?

ReplyDeleteGood question. The metrical (sacramental) records of St. Michael's GC Church in Sharon/Hermitage don't show anyone from that Zavadka (Ung/Už County), but they do show these families from Zavadka, Spiš:

DeleteKomar

Bosak

Vansač

Bučko

Pacak

Repasky

Šaršan

Zakucia

Benya

Geletka

Kubajko

Bučak

Turčan

Šveda

Jendrik

and probably others.