After doing the kind of research I first undertook three decades ago, which had not been seriously undertaken as a comprehensive look at Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants as a whole rather than only at one particular church jurisdiction/confession or in the context of a neighboring group with whom they sometimes identified, naturally I would start to get invitations to speak at genealogy conferences, Carpatho-Rusyn educational seminars, and churches. Eventually my work was being noticed by some prestigious entities and I was able to participate in scholarly conferences and some similarly notable venues. As I described in my previous post, in 2022 I was given the opportunity to create and deliver two papers/presentations, to two different audiences but both being prestigious in their own way.

The first I gave on August 30, as part of the Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center Summer Seminars series that continued the successful series of 2020 and 2021. The lineup was a mix of established professional scholars and Europe-based doctoral candidates; I suppose I fell somewhere in between, though the “independent” in “independent scholar” always suggested to me the idea of “lone wolf”!

- Unlikely Brothers: Carpathian Mountain Brigands and American Superheroes

Dr. Patricia Krafcik, Professor Emerita of The Evergreen State College - The Art of the Coal Region Renaissance: The Painter Anthony Kubek

Dr. Nicholas Kupensky, Associate Professor at the United States Air Force Academy - Lemko Art as an Artifact of Memory

Michał Szymko, Doctoral Candidate at Maria Curie-Skłodowska University - The Lemko Language as a Cure

Anna Maślana, Doctoral Candidate at Jagiellonian University

These were all great and we eagerly await their availability on YouTube. (I’ll update this post with the links when they are available.)

My presentation, ‘We’re Russian, But Not High Russian’: Flavors of Identity Among American Carpatho-Rusyns, was based on my paper from the 2021 Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) national convention in New Orleans. Freed from the strict 15-/20-minute constraints of reading a paper on a panel with 2 or even 3 other scholars, I was able to dig in a little more deeply and restore some of the passages I’d had to cut from the original paper.

Since the whole presentation recording’s posting is imminent (we hope), I’ll share here some of the highlights and hope that it moves you to watch the whole thing when it’s available.

In this presentation I analyze the various streams of Russophilism and other types of Rus’- identity among Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants to the United States and their descendants as it manifested in the naming and activities of their religious, fraternal, and social organizations as well as how they were known and written about in their local communities’ newspapers.

As I am wont to do, always having so much information I want to impart, I spoke for well over an hour. Fortunately, I didn’t lose too much of my audience, but the post-presentation feedback suggested that the main negative due to the length was that the audience wanted more time for engagement with me and each other through Q&A and discussion.

The following is a selection of the narrative and visuals from the presentation.

One Saturday afternoon in the mid-1990s, as I walked through the cemetery of a Ukrainian Catholic church in northeastern Pennsylvania on my first visit to the town to do fieldwork on the local Rusyn and Ukrainian immigrant community’s history, I encountered some elderly members of the church tending to family graves. As I was surveying the names of those buried there, they inquired about my visit to their town and parish cemetery. After giving them an “elevator speech” about the goal of my research, they wished me well and sent me off with “Do our Russian people proud!” I thought that was an odd thing to hear from people who were raised in an ostensibly Ukrainian Catholic church, until I made my way down the hill to photograph the church and its cornerstone.

Inscribed on that stone was an equally surprising series of words:

– words that helped me understand the good wishes of those parishioners in the cemetery.

After much research on this community that began that day, I learned that their parish, Ukrainian Catholic by ecclesial affiliation, was composed of the descendants of immigrants from the Lemko and Prešov Regions of Carpathian Rus’, with but a small Galician Ukrainian element which, despite the parish’s official status as Ukrainian, did not steer them away from a Russophile course that had begun even before the parish was established in 1905.

But what kind of “Russians” did those parishioners think they were, and how, 75 or more years since their parents arrived in the United States, was this identity still viable? In this talk, I will analyze Russophilism in its various streams among Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants to the United States as it manifested in their religious, fraternal, and social organizations and serial publications. It will also look at the ways a Russian identity was expressed not just within the community but to the general public at large. Finally, it will assess to what extent and in what ways a Russian identity may persist to the present among individuals of Carpatho-Rusyn descent and their traditional institutions.

Early in the life of Minneapolis’s newly-transitioned Orthodox parish, composed almost entirely of Carpatho-Rusyns, its choir director/school teacher noted “there was not a single man from Russia in the city of Minneapolis” (Paul Zaichenko, in Golden Anniversary Souvenir Album – St. Mary’s Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church A Capella Choir, 1941). Zaichenko, a native of the Russian Empire (and by his surname we could say he was probably an ethnic Ukrainian), probably considered himself the lone exception to this except for the parish priest, because in the Minneapolis church, all but four of its first twelve pastors—and all but one of Zaichenko’s first ten choir director successors—would be of Russian origin.

We’re going to talk for a bit now about Russophiles and Russophilism, and the types of Russophilism manifested in the American Carpatho-Rusyn community. While Russophilism was promoted among adherents (converts and their descendants) of the Russian Orthodox Church, it was also a significant factor in the Greek Catholic Church and in fraternal organizations, some of which were church-affiliated and others which more political and cultural in nature.

According to Paul R. Magocsi, Russophiles in the American context could have been ethnic Carpatho-Rusyns or Eastern Slavs from the former Russian Empire.

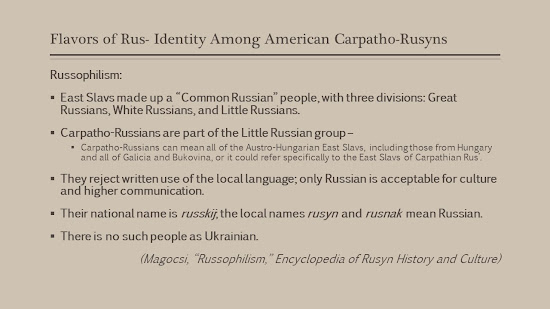

The principles of the Russophile ideology were:

- East Slavs make up a “Common Russian” people, with three divisions: Great Russians, White Russians, and Little Russians. White Russians would be the people known today as Belarusians, while Little Russians are generally the same people known today as Ukrainians. In addition, Russophiles believed that:

- Carpatho-Russians (karpatorossy) are part of the Little Russian group –

- Carpatho-Russians can mean all of the East Slavs of Austro-Hungary, including those from Hungary and all of Galicia and Bukovina, or it could refer specifically to the East Slavs of Carpathian Rus’ (which raises the question, where and/or what is Carpatho-Russia? – which again may or may not be limited to what we today call the Carpatho-Rusyn homeland, depending on who was using the term Carpatho-Russia)

- Additional Russophile principles: They reject written use of the local language (the village dialects naturally spoken by ordinary people); only Russian is acceptable for culture and higher communication.

- Their national name is russkii; the local names rusyn and rusnak mean Russian.

- Finally, there is no such people as Ukrainian.

A related position, but one which was did not last very long among the U.S. immigration, was the Old Ruthenian: it recognized a unity of East Slavs who called themselves Rusyns (that is, historical Ruthenians) within the Habsburg Empire and Austria-Hungary, and whose affinity with the East was with the spiritual culture of Holy Rus’, as it subsisted within the Greek Catholic Church locally, in Austria-Hungary, and within the Orthodox Church more broadly. In the U.S. as it was in the homeland as well, by the start of the 20th century it was supplanted by Russophilism or quashed by Ukrainianism, where it had existed in both cases only among Galician Rusyns, mainly Lemkos, after a brief period early in the immigration when reading rooms affiliated with the Old-Ruthenian organization based in Austrian Galicia, the Michael Kachkovskii Society, were established in a few Lemko Rusyn immigrant communities, mainly in Pennsylvania and Connecticut.

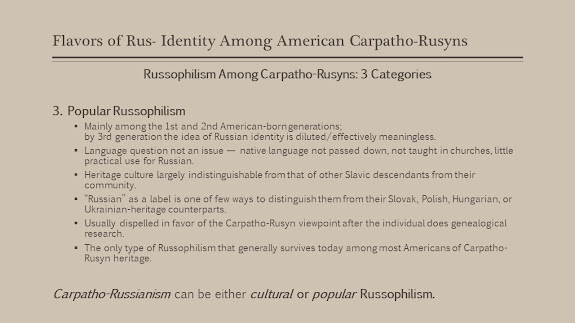

From my observations of the Carpatho-Rusyn immigration in the U.S., I would like to propose further categories of Russophile belief and behavior: Classical, Cultural, and Popular Russophilism.

Carpatho-Russianism substitutes the term Carpatho-Russian for Russian as an endonym but has varieties that fit into either the cultural or the popular Russophilism categories. These are:

- Promotes particular Carpatho-Russian, regional history but in a Common Russian context as well as promotes Russian language, yet prefers the Carpatho-Russian label over Russian. In other words, a type of cultural Russophilism. This can be traced to the 1920s in a Greek Catholic setting and certain clergymen and influential laymen (e.g., Fr. Michael Staurovsky and Michael Roman). (It predated the formation of the Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese.)

- Equally accepts the validity of the labels Carpatho-Russian and Rusin (usually rejecting “Rusyn” and “Carpatho-Rusyn”, however), which was essentially the position of influential clergymen and laymen like Msgr. John Yurcisin of the Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese and Michael Roman of the Greek Catholic Union.

- Carpatho-Russian as a preferred synonym, but a synonym nonetheless, for Carpatho-Rusyn.

Influence of the Russian Orthodox Church

The fundamental points of Russification of the religious customs of Rusyns who joined the Orthodox Church in the period 1891-1920 were:- Replacement of congregational singing (chiefly the Subcarpathian prostopinie plainchant, but also Galician samoilka plainchant in majority-Lemko parishes) with choral music;

- Adopting of the Russian pronunciation of Church Slavonic—so instead of “Hospodi pomilui” it’s “Gospodi pomilui” and instead of “Mnohaia lita” it’s “Mnogaia leta”, and such;

- Suppression of paraliturgical devotional hymns before and after liturgical services or during pilgrimages, as well as most Christmas carols (except for a handful of what are considered “canonical” carols, e.g., Boh predvichnyi and Nebo i zemlia), which though they are thought of by many as typically Carpatho-Rusyn or Ukrainian, can be heard even in Russia.

We can note, however, some majority-Subcarpathian Orthodox parishes (e.g., Berwick, Black Lick, Colver, Curtisville, Masontown, Monessen, Monongahela, Nanticoke, New Salem, Portage, and Vintondale in Pennsylvania) that were organized between 1909-1920—especially during the episcopacy of Bishop Stephen (Alexander Dzubay) of Pittsburgh—did employ cantors and retained prostopinie, some as late as the 1990s (New Salem). We know of a few parishes organized in the 1920s under the Metropolia which also retained prostopinie: Passaic, N.J. (St. John the Baptist, under Prof. Michael Hilko) and Crossingville, Pa. And some collections of Russian Orthodox church music published in the United States in the last half-century have included a few prostopinie settings, although usually in four-part harmony still intended for choral singing.

Cultural practices outside of the liturgical setting also experienced Russification. Some parishes were home to a balalaika orchestra (Minneapolis and Pittsburgh, Nanticoke, and Edwardsville, Pa., among others), an iconic Russian instrument decidedly unknown in Carpathian Rus’.

The Christmas celebration which in Europe had been marked by strolling carolers (yaslichkari) conducting a Nativity play with memorable characters like the “guba” shepherd who scared many a young child, was replaced with the Russian-origin ёlka (yolka – literally, Christmas tree), still a dramatic performance but without the native elements of Carpatho-Rusyn culture. (The yaslichkari were not unknown in the Russian Orthodox setting, although it was the very same handful of parishes that preserved congregational prostopinie which were more likely to have the custom. Here I’m showing several of these groups.)

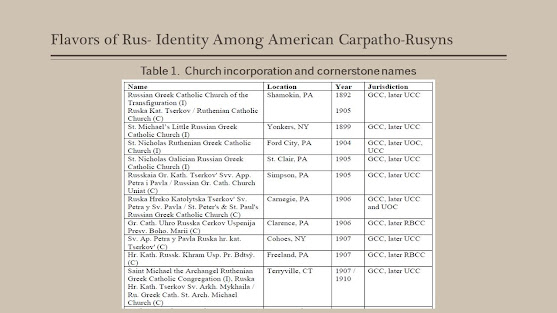

To evaluate the existence of Russian identity tied directly to the Church, I compiled names of various Carpatho-Rusyn-founded parishes that had some variety of rus- in their names (including Ruthenian, for comparison) in their legal incorporation or as used on their cornerstones. (A caveat here – since most Russian Orthodox parishes formed under the Metropolia followed a more or less standard naming convention of “Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church,” those are omitted since there isn’t much to be gleaned from it.) Note that the table is not comprehensive, but was compiled from whatever sources I had available in my own archives or online. For the sake of this presentation I’m just showing a subset of the total data I compiled.

Sometimes the cornerstones of these churches had a slightly different name than was used in their legal incorporation, and usually they didn’t only have the church name in English. We can see that virtually all Carpatho-Rusyn-founded church names/cornerstones with an ethnic identifier used russka, russkaia, or ruska, or in English, Russian.

Names Used by Carpatho-Rusyn Secular / Fraternal Organizations

Continuing with analysis of ethnonyms and language, all the major Russophile organizations’ periodicals I had available to survey shied away from using a one-word ethnonym for their members, opting instead for adjectival forms like russkii narod or karpatorusskii narod, even in the same sentence where such ethnonyms were used for their ethnic neighbors:

“Karpatorusskij narod majet mnoho jazykovych dialektov, raznych slov, kotore ani Slovak, ani Čech, ani Veliko-Rus, ne porozumit.” [The Carpatho-Russian nation/people have many linguistic dialects, various words, which neither a Slovak, Czech, nor Great Russian can understand.]

That’s from the Pittsburgh American Rusyn Orthodox newspaper Russkii Vistnik, in 1923. (And here I looked mainly at editorials; newspaper correspondents may well have used noun forms in their letters, even “Rusiny”.)

While one could argue the national fraternal societies and their print organs were in the hands of intelligentsia who had a more developed (and more committed) sense of ethnonational identity than did their less-educated and blue-collar members, it is with the nomenclature used for local community organizations that a truer sense of the identity of the rank-and-file immigrants is revealed.

In Table 2, I compiled lists of names, by legal incorporation documents where possible or from English-language newspaper articles and advertisements, of such organizations founded by Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants and their American-born children through the end of the 1940s, with some variant of Rus- (including Ruthenian). From this we can make the following observations.

The clearly dominant term used to name these organizations was Russian, from the earliest days (1886) at least through 1940 (although increasingly less so, in favor of Carpatho-Russian). The term was applied to local fraternal brotherhoods/sisterhoods, so-called citizens’ clubs, cultural organizations, and even a fire company.

Unlike some of the other terms, “Russian” did not denote any particular religious affiliation. It was also combined with Slovak or Slavonian, for example, “Russian-Slovak Citizens Club.” The non-English term Russky even found its way into a few organizations’ names as late as 1941.

Rusin, with an ‘i', did not appear in this English-language context until 1919 but was well represented thereafter through the 1930s; these organizations were almost exclusively connected in some way with the Greek Catholic Church, even if not explicitly implied in their titles. Uhro-Rusin or Hungaro-Russian were used twice in 1917 foundations and one Uhro-Russian Club founded later. Carpatho-Rusin was actually an innovation in English, appearing only once in the entire table, around 1940.

The term Little Russian was used for only a handful of organizations, ones founded between 1898-1903. Its ideological successor Ruthenian, at least for those who were developing a Ukrainian ethnonational orientation, was confined to foundations between 1910-1917, and was never associated with an organization in any way affiliated with the Subcarpathian jurisdiction of the Greek Catholic Church. This could be surprising for a generation of Byzantine Catholics of Rusyn heritage who in their church publications would see their ethnic background described as Ruthenian or Carpatho-Ruthenian.

Carpatho-Russian was a relatively late entry into this assortment, in 1917, but gained traction and was quite widely used into the 1940s and even afterward, at least until the Second Red Scare ramped up, which we will discuss later.

Nomenclature about Carpatho-Rusyns as used in the American Local Press

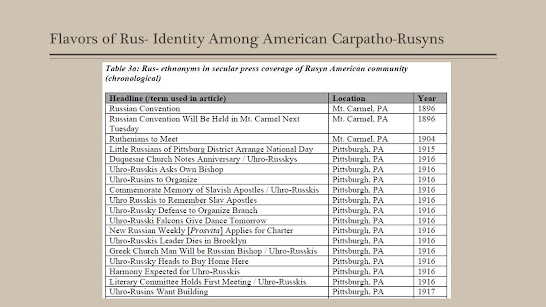

Beyond the ideologically-controlled environment of the Carpatho-Rusyn community newspapers, the largest and most widely read of which were published by the fraternal organizations, another manner of individuals expressing their identity was to their American neighbors via local press reporting. I compiled a list of representative news articles (Tables 3a, 3b) on Carpatho-Rusyn community activities, with the term(s) used to describe the community. The terms’ occurrence and frequency followed fairly closely those of the prior tables on church incorporations and especially organization names. Again, Russian was the clear preference, with Carpatho-Russian following.

Russian was the first Rus- ethnonym to appear, in 1896; its use continued until it began to fade in the 1930s except when linked specifically with the Russian Orthodox Church. The notable exception was the practice in the Pittsburgh area in 1916-1919 to refer to Uhro-Russky/Uhro-Russkis and then Uhro-Rusins.

Carpatho-Russian began to appear in 1918, when covering the same communities that had been referred to in Pittsburgh as Uhro-Rusin the year before.

Carpatho-Rusin first appeared in 1918, but was quickly supplanted by Rusin until the late 1930s, when Carpatho-Russian began to dominate.

In a Carpatho-Rusyn context, Ruthenian was used rarely between 1904-1925. The precursor to it, Little Russian, was used even less, and in 1915 surprisingly was the term that described Rusyns from Hungary in the Pittsburgh area, in the same paper that in 1916 switched to Uhro-Russky and Uhro-Rusin.

– If this makes you want to hear more, please stay tuned for news about the full presentation recording. There is certainly more to be explored, some of it provocative, even shocking. And of course I give an assessment of where things stand today after the “Roots Fever” of the 1970s that prompted a Carpatho-Rusyn revival in the United States.

Original material is © by the author, Richard D. Custer; all rights reserved.

I am always amazed at the work you do to help everyone sort through the uncertain confusion of our people Rich..

ReplyDeleteThank you for the work you do,

Денис Галушка

Thanks for the kind words, Dennis!

DeleteEnjoy reading your posts and impressed with the content. Pleased about the way you keep the posts up to date.

ReplyDeleteMy father is from Olyphant, then moved to Throop, and my mother is from Dunmore. Our roots are in Austria-Hungary (Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria) and Slovakia, at the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, based on the documents in my possession. My great grandfather (born 1845), and grandfather (born 1888) are from the village Bednarka, Lipinki, present day Poland but I'm unable to locate records from my mother's side in Slovakia.

During family gatherings at Christmas (Dec 25 + Jan 7), and on Easter, my aunt would share a few stories of family history with me. I do remember her animosity towards citizens from Russia, Poland, and Germany because of the family stories shared about the way they mistreated (to put it nicely) our family. Our family were commoners desiring to live peacefully and prosper, to the best of my knowledge. The borders constantly shifted and with no industry development to prevent poverty and sickness the land of my ancestors was engulfed in unbearable hardship.

In closing, the history I've read in your posts have been helpful to better understand why our ancestors decided to leave the old homeland to pursue the new homeland. Keep'em coming!

Rich,

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for all you do. Your work hits so close to home

for me. My grandparents all came from Galicia between 1890s up til

about 1905. Before WW1. Before any of the big Ukrainian nationalistic

movement. They came from Cieplice, and Losha in the Lemko areas,

and Stanislav (Ivano Frank) and Probuzna. They all lived in NY, NJ, and

most ended up near Jessup and Olyphant. My grandparents told me I

was Russian. And when Ukraine was mentioned, they told me Ukrainians and Russians are the same people and the same country.

I was born in 1961 and as such have identified as Russian. Growing up

It was my identity and it came from my grandparents. Proudly. It may

Be unpopular nowadays in this horrid hateful era where Russian or

Ukrainian or Rusyn brothers kill each other. But that is my story. There

was no country named Ukraine until 1991 when I turned 30. And I could

never identify with the hatred that the new generation of that country promotes and lives for. I also never heard of the term Rusyn or Rusin,

until a few years ago. It was never part of my family. The families named

Nagurney, Nagorny, Synytszyn, Werchanowska, and Ukrainiec. Your

research is the first that rather tells my exact story here. Thank you.

I would enjoy communicating more with you.

Peter Nagurney

Bridgeport, Ny

I ran across your interesting blog while researching the history of PA ancestors who originally came from the area near Mukachevo in the Sub/Transcarpathian area. They worked in the coal mines and steel mills around PA. Most settled around Duquesne. Good luck with the project.

ReplyDelete